Women who worked for NSA were pioneers in computing

Interviews compiled by Eileen Buckholtz

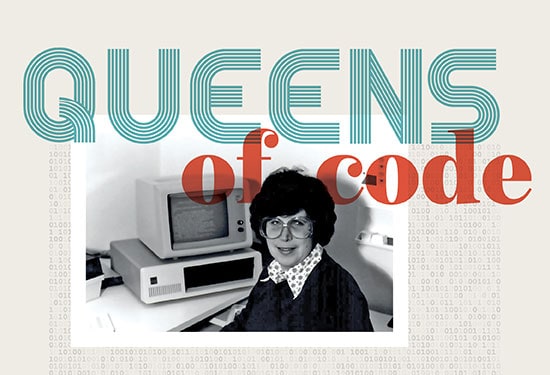

They look like your grandmothers and great aunts. But the Queens of Code, a group of women from Howard and nearby counties, share a secret they have been safeguarding for more than 50 years. They were all computer and technology pioneers who worked at the National Security Agency (NSA) in the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. Because these women’s jobs were often top secret, working on the most sensitive national security programs, they couldn’t discuss what they did, even with their families; in many cases, they couldn’t even confirm they worked there. And their existence has been hidden for more than half a century.

The Queens of Code along with their NSA colleagues and industry partners, made significant advances in technology. Their work brought about faster and more powerful mainframe and super computers, large scale data storage and retrieval (including developing read/write CD ROMS), higher capacity tape storage, and magnetic drum disks. The group contributed to Internet (which began as the ARPANET) and networking capabilities, multi-programming and processing, database management, programming languages, computer and cyber security, global digital networking, machine translation research that became part of popular word processing systems, search software, telecommunications, super conductor chip design, and more.

Back in the 1950s and early ‘60s when career choices were limited for women—teacher, librarian, nurse, secretary, beautician, and homemaker headed the list—going into technical fields was uncharted territory and such a choice wasn’t always encouraged. Some of us majored in math and science, others in language, philosophy, or music. And we were some of the first graduates who earned degrees in computer science in the country.

Many of the group we refer to as Queens of Code were recruited by NSA during the height of the Vietnam War when government and Defense Department agencies were less than welcome on some campuses. Surprisingly, our academic advisors suggested that we interview with the little-known agency. The recruiters were vague but intriguing, “We can’t tell you what you’ll be doing—except you’ll work with the latest technology—and you’ll love it.” And we did, having careers in technology that lasted for 30, 40, and even 50 years. The jobs promised us equal starting salaries to the guys, a rarity back then, and they’d also pay for our graduate studies.

In the early days, NSA had the most sophisticated computers in the world, as well as the most challenging information processing requirements. By 1968, the agency had more than 100 computers spread over five acres of computer rooms at a time when most companies had one or none. The inventory increased rapidly over the next decades as our big data processing needs grew and many of the fledging companies we partnered with have grown into the tech giants of today. The Queens of Code numbered less than 150—only about 10-15 percent of the technology workforce, so frequently one of us might be the only female in a meeting—or even the only professional woman in our office. Fortunately, most of our male co-workers were supportive as we worked alongside them. And there was also a cadre of women mentors (our legacy Queens) who had worked for the agency’s predecessor during WWII.

Until now most women’s contributions to technology have been left out of the story. But we want girls and young women to know that if their grandmothers and great aunts could have exciting, rewarding, and well-paying careers in tech, so can they. NSA worked to recruit, develop, and retain their computing women after learning from their experience with the Code Girls during World War II that women were a valuable asset. Of course, there were some struggles along the way, but the Queens of Code made a big impact on NSA’s technology and mission.

Here are some stories about our early days, when most of us were in our early 20s.

Eileen Buckholtz

In 1970 my first data systems intern assignment was in an applications group working on the Univac 494 computer. Our systems had to run 24/7 because the jobs were coming in real-time and the lives of our military were on the line. The files would sometimes get corrupted and then error-off the system. I developed a FORTRAN program that would check for file issues and then alert the operators to intervene before the system crashed. This program greatly improved the stability of the system, and it ran for many years.

In 1970 my first data systems intern assignment was in an applications group working on the Univac 494 computer. Our systems had to run 24/7 because the jobs were coming in real-time and the lives of our military were on the line. The files would sometimes get corrupted and then error-off the system. I developed a FORTRAN program that would check for file issues and then alert the operators to intervene before the system crashed. This program greatly improved the stability of the system, and it ran for many years.

To submit your card deck and pick up your printouts, you had to venture down into the bowels of the basement, which was a maze of dimly lit halls with the same grey doors sporting signs that warned, “only authorized personnel allowed.” One of my co-workers showed me the secret to not getting lost—just follow the line someone had drawn from our office, down the stairwell, and through a windy path in the basement that ended up at our computer room. I felt confident for months—until the morning we came in and they had painted all the walls, stairwells, and even the basement. Our safe line trail was gone; it seemed like some people wandered around in the basement for days.

Kathy Jackson

In 1967 as a newly minted data systems intern trained as a FORTRAN programmer, I was ready to start my career at NSA, having been assigned to an office for a nine-month tour. The first morning when I arrived at the office, expecting a warm welcome from a team that I was sure could use my expertise, I found that they were disappointed that I had arrived because they needed my vacant desk to store gifts for a baby shower scheduled for lunchtime! Overcoming my initial disappointment at not being warmly welcomed, I proceeded to investigate what kind of programming support they needed. That led to an interesting introduction to the world of computers at NSA.

In 1967 as a newly minted data systems intern trained as a FORTRAN programmer, I was ready to start my career at NSA, having been assigned to an office for a nine-month tour. The first morning when I arrived at the office, expecting a warm welcome from a team that I was sure could use my expertise, I found that they were disappointed that I had arrived because they needed my vacant desk to store gifts for a baby shower scheduled for lunchtime! Overcoming my initial disappointment at not being warmly welcomed, I proceeded to investigate what kind of programming support they needed. That led to an interesting introduction to the world of computers at NSA.

The next step in my orientation was a tour of the basement, a huge area where the computer I would be using, the UNIVAC 1108, was located. My job was to remove computer printouts from one of the printers, review the data, look for data anomalies, and adjust the FORTRAN software to fix them. It seemed challenging and interesting at first, but as the days and weeks rolled by reviewing rows and rows of 1’s and 0’s became a little tedious to put it mildly. Years later I learned just how critical that data was to national security.

Lois A. Gutman

My research career plans vanished in a phone call. Former President Nixon had cut federal research grants and after moving from Michigan to New York, I was told that I wouldn’t be able to start my new job the following Monday. I ended up working in health insurance claims fraud, hitting a glass ceiling in one year. I changed companies, did well, but knew I’d never be happy long-term. A Baltimore native, curious about NSA, I applied, was told “trust me, you’ll like the work” and received an offer letter to start employment in 1978 in the cryptanalysis intern program. I loved it! Each six-month tour in the three-year training program was different, interesting and rewarding.

My research career plans vanished in a phone call. Former President Nixon had cut federal research grants and after moving from Michigan to New York, I was told that I wouldn’t be able to start my new job the following Monday. I ended up working in health insurance claims fraud, hitting a glass ceiling in one year. I changed companies, did well, but knew I’d never be happy long-term. A Baltimore native, curious about NSA, I applied, was told “trust me, you’ll like the work” and received an offer letter to start employment in 1978 in the cryptanalysis intern program. I loved it! Each six-month tour in the three-year training program was different, interesting and rewarding.

Maureen McHugh

I started at NSA in August of 1969. After finishing the six-week orientation program for newly hired mathematicians, I was selected to go into the data systems intern program and was assigned to a small section doing computer support for cryptanalysts and mathematicians researching Soviet cryptosystems. The timing couldn’t have been better. I got my clearances just at the time the organization was getting its first supercomputer, a CDC 6600, designed by Seymour Cray, the father of supercomputers. Primarily a research organization, this center was at the cutting edge of newly developed software and support tools. IDASYS was the operating system. It was interactive! No more punched cards! I slowly learned COMPASS, the machine language for the CDC 6600 and wrote a few programs. After that, I worked closely with the system manager (a new term in 1969 which would morph to system administrator a few years later) to learn how to use the system, keep it in top operational order, and get new users started on the system. I loved this assignment and remember well in the fall of 1969 talking to some of my female coworkers about another first in the workplace. In late October several of us wore pantsuits to the Agency for the first time. We got some looks in the cafeteria and halls, but no negative comments from our supervisors. We never looked back.

Peggy Strader

When I started at NSA in 1968, we were introduced through short courses to the various disciplines that NSA required. I was fortunate to be offered several internships and ultimately chose computer systems. The internship was invaluable in preparing me to become a computer systems analyst.

When I started at NSA in 1968, we were introduced through short courses to the various disciplines that NSA required. I was fortunate to be offered several internships and ultimately chose computer systems. The internship was invaluable in preparing me to become a computer systems analyst.

My first assignment/tour as an intern was the Applications Quick Response Group. On this assignment besides taking courses to learn FORTRAN and COBOL

I was responsible for running jobs on the IBM 360/20 and early IBM 370s. Back in those days we ran jobs by loading trays of punched cards (Hollerith cards) into the card readers which would then interpret the punches for codes to use to retrieve data or run a program to produce a listing which then would be returned to the user/customer. It was way before the time where you could initiate a program or retrieval from your desktop. During this time, I learned much about magnetic media, JCL Job Control Language, and PAL Procedure Assembly Language. The IBM 370 came in during this tour, which was much faster than the IBM 360.