COLUMBIA’S FIRST RESIDENTS DISCUSS THEIR CHOICES FOR AN ORAL HISTORY PROJECT

Anne Haddad

March 2017/April 2017

A new city, with new homes, invited a new breed of American pioneers to build on the original idea of the Westward Expansion, right here in the East, and no need for roughing it with covered wagons. The flat fields and gentle rolling hills waiting for them  already had newly built houses, villages and highways that extended into two major cities.

already had newly built houses, villages and highways that extended into two major cities.

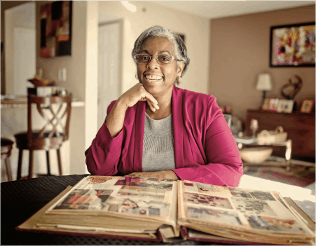

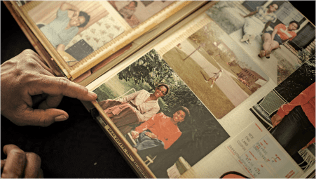

When developer and visionary James Rouse created it in 1967, Columbia sounded like a dream to Doris Ligon and her husband. They were African-American Baltimore natives with a young family. He was scheduled to return from Vietnam in 1969 and begin a doctoral program at the University of Maryland (UMD) in College Park. They read about Rouse’s vision of socioeconomic and racial diversity and community. It sounded too good to be true, especially in the midst of the block-busting white flight afflicting Baltimore. Ligon hadn’t thought anyone in Howard County would sell homes to African-Americans, much less welcome them.

“Remember now this in 1960s,” she says. “I thought, this doesn’t sound exactly right.” Ligon admits that she and her husband were skeptics. “Well, I was, more than my husband,” she says. “I said it can’t be, but we found it to be true. We chose the life and got the house.” They still own that first home, and her son now lives there. Ligon relayed her story in an interview recorded last year as part of an oral history project conducted by Columbia Association (CA) and anthropology students at UMD. The residents interviewed all volunteered and signed waivers for their comments to be part of the project. The interviews will eventually be published by CA as part of Columbia’s 50th “birthday” celebration later this year.

“My first impressions were skeptical … until we met Mr. Rouse and we came to the village center and we looked at all the properties. It was nothing but positive,” Ligon told the student who interviewed her. Now, nearly five decades later, she divides her time between Columbia and North Carolina, where her daughter and grandchildren settled. But she still calls Columbia home a nd spends as much time there as she can.

nd spends as much time there as she can.

Columbia Association made 480 pages of interview transcripts available to “Her Mind” magazine. We provide some excerpts here, with only minor edits to correct spelling, punctuation and grammar errors resulting from raw transcription.

From reading through several, a pattern became clear.

First of all, many of those interviewed— whether they were African-American, Caucasian, immigrants from India, immigrants from Ireland, Jewish, Christian, Zoroastrian or nonreligious (to name a few of the ways the participants described themselves)—said they moved to Columbia expressly because of Rouse’s vision of diversity and quality of life.

Nearly all mentioned the school system as a huge draw, both for its quality and for student diversity.

The cluster mailboxes, walking paths, parks and other common spaces not only attracted residents, but kept them connected to each other and provided a sense of community.

Fifty years ago, what is now Columbia’s familiar blend of the three great qualifiers in modern city planning—urban, suburban and exurban—was a complex, occasionally fitful array of architectural drawings, plot maps, position papers, legal documents and minutes from public meetings. Rouse and other like-minded activists saw cities and towns in the region struggling with poverty and segregated neighborhoods. The idea of a new city—Columbia, not all that far from Baltimore and Washington but structured differently, governed differently— was more than possible. It was probable. Soon it was a reality.

A half century later, what do people who lived here, raised children here and worked here, have to say about their hometown?

Some, like Mary Donegan, have been in love with Columbia from the first.

“We moved to Columbia [in 1969] because my husband worked for The Rouse Company in Baltimore. We moved out to this new  city, which we were really excited about. I believe that there were only about 4,000 people here when we came and it was a wonderful free experience. Nobody had a history in Columbia, so we were making history when we came. There was no established group of people; everybody was starting from scratch and we had a neighborhood with janitors, mailmen, and lawyers, doctors all living on the same street. Great way to live.”

city, which we were really excited about. I believe that there were only about 4,000 people here when we came and it was a wonderful free experience. Nobody had a history in Columbia, so we were making history when we came. There was no established group of people; everybody was starting from scratch and we had a neighborhood with janitors, mailmen, and lawyers, doctors all living on the same street. Great way to live.”

Donegan fondly recalls the public schools attended by her children—intellectually engaging, so different from the ones she attended in her native Ireland.

“I had gone to school in Ireland and Catholic school where you sat at a desk and you did not move out of your desk most of the time,” she says. “We came to Columbia … and we saw the kids lying on carpets on their tummies. That’s how they were learning, with a tank with fish and I think there might have been an iguana there. And I thought, ‘Wow, this is the way to go to school.’”

As much as they loved Columbia, she and her family missed Ireland. So they decided to go back. But their next move speaks volumes about the little central Maryland community:

“We stayed [in Ireland] for one year and said, ‘Uh, no.’ We loved the atmosphere in Columbia and the wonderful neighbors we had and this great spirit of the city so we came right back to Columbia for the second time. Cost a little bit more to buy a house, but that was fine. The kids went right back to school and people said ‘Weren’t you gone some place?’ and I said, ‘Yes, we were, but we are back.’ ”

Learning about Columbia’s residents and how their experiences affected their lives is eye-opening—and that’s why L. Jen Shaffer, assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and her colleagues at the Partnership for Action Learning in Sustainability (PALS) at the university’s National Center for Smart Growth undertook an oral history of these men and women.

“Columbia Association put out an announcement that they were looking for a diversity of folks to interview regarding their experiences in Columbia for the 50th anniversary celebrations,” Shaffer says.

The CA, Shaffer explained, went through its archives and found a pool of interview candidates—an equal number of men and women, various races and ethnicities, young and old, new and long-time residents, and a fair representation of economic backgrounds. More than 70 residents volunteered, although a smaller number were actually interviewed. PALS and Shaffer’s students conducted the oral history project less as a sociological study and more as a gathering of impressions. The result, she says, is an expression of deepseated love for community.

“All of the residents our class interviewed love Columbia,” Shaffer says. “It is most obvious in those folks who moved away at one point but then moved back to Columbia. While they might have been warmly welcomed in the other community, it just wasn’t home, it wasn’t Columbia.”

Blondelle Hunter, for example, typifies the positivity that long-timers have about the community. A teacher at Wilde Lake High School for much of her life, she and her husband were living in Washington, D.C., when they first read about Columbia in a newspaper article.

“We were just beginning our family,” Hunter told the PALS interviewer, explaining that their initial attraction to the new city was based in their desire to raise their children in a safe environment.

Columbia “sounded ideal, and from our beginning until now—even though things have changed and you accept change—what [James Rouse] had wanted for this community was very inviting to us and has proven to be, on a large scale, exactly what he had anticipated.”

Hunter, who calls herself a “people person,” says the Columbia model of integrating economic groups gives children from different backgrounds the opportunity to learn and grow together.

“To see children really not being aware of their economic status, but still being able to be involved, it’s very important,” Hunter says. “I like talking to people and not knowing … their economic status and maybe later finding out that they’ve had some hardships but it didn’t matter … based on our ability to communicate, to socialize.”

Many of the residents interviewed—such as Valerie Montague and Christiana Rigby —grew up in Columbia and then moved back to raise their own families. They are of different generations, but had similar experiences of finding the city a little frustrating as teens, then growing to appreciate it more and returning to raise their own children here. Both now play an active role in local boards and cultural organizations.

Valerie Montague first moved to Columbia in June 1973 with her parents and sister. She currently lives in the village of Kings Contrivance and previously lived in the villages of Wilde Lake and Hickory Ridge. Open space is important to her, and she enjoys the community’s festivals, concerts and nature trails. She ran track at Wilde Lake High School and both of her daughters also were athletes there. They are now in graduate school in Texas and West Virginia.

“When I first moved here, I was 16, and I’d come from Washington, D.C., so I thought Columbia was rather boring because you couldn’t really get anywhere without a car. You had to know somebody and go visit them at their home.

“I went to college, lived in [Boston and] a couple other places and then, when I got married, I moved back here into what had been my parents’ house. After my father passed away, my mother sold the house to me and my then-husband. My daughters grew up in that same house.

“…I liked the idea of raising kids in Columbia. The public schools are very good. But also because the kids were going to be biracial—the man I married is Caucasian. So Columbia has a reputation for being very tolerant, very racially tolerant, and I thought it would be easier for them to grow up here than most other places.

“One of my daughters went on a high school exchange. Columbia has three sister cities: one in France, one in Spain and one in Ghana. I’ve had an opportunity to visit the one at Ghana and actually help form that relationship and to visit the one that’s in France, as well. My daughter went on CA’s sister-city exchange program to the sister city in Spain. So, international culture, local culture, black culture, it’s all here.” [Editor’s note: Columbia added a fourth sister city—Cap-Haitien, Haiti, in 2016, see page 13.]

Concerts, movies and cultural events— especially outdoors—make for a good life, she says. “In the summer, I keep a folding chair in my car trunk. So that if I want to go to the lakefront and enjoy any of the free things they have, I can,” she adds.

“Rouse’s thing was ‘do well by doing good,’ to be financially profitable by treating people well and doing the right thing. I don’t think his goals changed. I guess I just understood him better as times went on, but he always wanted to do well financially by doing good. And I thought that was a really good value to have,” Montague says.

Her one concern is that Columbia has grown harder for people to afford.

“Rouse seemed, from what I’ve read—I never knew him personally—to be very interested in making sure that people of a variety of income levels could afford to live [in Columbia]. That seems to have gotten lost. There seems to be much more of a push for wealthier people.” Montague worries that new housing seems to skew toward the more expensive stock, and the same goes for retail outlets. “There’s the income shift; it seems to be going toward the higher end,” she says.

Montague chairs CA’s International and Multicultural Advisory Committee and is a member and past board member of the League of Women Voters. “And I truly enjoy the role of moderating candidates’ forums,” she says.

Her main concern in local government is education—which has served her and her daughters well.

“As long as [county elected officials] continue to appropriately fund education, I’m happy. The schools are able to prepare students regardless of where the students are from. And I mean academically, emotionally, intellectually. They attract good teachers who hold them to high standards, and the parents are holding the schools accountable,” Montague says.

Christiana Rigby, now in her early 30s, grew up in the Kings Contrivance village in Columbia and eventually moved back with her husband to start a family. She hopes her young daughter will have the same experiences she loved—playing soccer in a neighborhood field and spending time at the neighborhood pool.

“I graduated college and then I moved to Tucson and then Miami. I met my husband in the interim and I moved to England for a while because that is where he is from. Then we lived in D.C. for a few years before deciding to ultimately settle in Columbia [in 2012]. My parents still live here. My sister bought a house in Oakland Mills and we just really wanted to be close to the family.”

Rigby, who is white, said “I really wanted to make sure we were moving to a diverse area. Growing up, I had friends who lived in apartments and friends who lived in town houses and friends who lived on horse farms. It wasn’t until I started making friends with people in high school who grew up outside of Howard County, that (I learned) those experiences were more unique than I realized,” she says.

Rigby says her feelings about her hometown changed over the years. In fact, at first she didn’t want to move back to Columbia, but it was her British husband who convinced her it was the ideal place for them to start a family. They now have a young daughter.

“When you are younger and in elementary school it is so great because your friends live near you and there are always so many kids the same age. The best year was when you were 9, because then you could go to the pool by yourself,” Rigby says.

“Then towards high school, I remember it just felt really stifling because everything stopped at like 9 o’clock and you couldn’t get anywhere on your own and your parents had to drive you everywhere. I remember just wanting this sense of escapism to go to Baltimore, to D.C., and to just get out. So it is really funny to me, knowing we used to call it ‘the Columbubble,’ and I would tell my parents how awful they were for moving to such a boring place,” Rigby says. “I also have involved myself a bit more: I volunteer. I ran for the village board, so now I get to work with the residents and be their advocate, and it is just a very different experience then when you are a kid.”

Rigby says she believes that organizing village events is a way to foster connections among residents in a way that enlarges their social circles. “If I had to boil down what I thought was really important in Columbia, it is that connection to neighbors and that engagement with people. I think sometimes our social circles tend to be small—the people you go to school with it, the people you work with—and I think that having that engagement with a lot of your neighbors is really important.”

Marla Stahl, who describes herself as coming from an interracial family, has Caucasian, African-American and Native American ancestry. She moved to Columbia nearly 40 years ago. Columbia was the first community she visited when she started looking for a house, and she hadn’t even heard of Rouse’s vision at the time, but she noticed that there were interracial families, and everyone seemed comfortable with everyone else.

“They asked me if I wanted to check out those two other towns, I’m like, ‘No, no. This is it. This is where I’m staying. And it just felt like home,” Stahl says. “I didn’t know anybody. [But] I went down to Lake Kittamaqundi and it was October and I just remember seeing these beautiful orange trees across Route 29 and just looking at all these families. I said ‘I want to raise a family here.’ And I did. And so I have this tie to downtown Columbia.”

Michele Gay-Crosby, in her mid-40s, was interviewed with her father, Willis Gay. Both Gay and his wife still live in Columbia.

“I actually moved to Columbia twice. Once in 1976 with my mom, dad and my sister, but after college I moved away and I moved back recently with my family in 2013,” Gay-Crosby says.

“I went to college in Virginia and after I graduated, I worked in Washington, D.C., for a while and I went to graduate school in Chicago. And after that, I lived in Prince George’s County for about 14 years.”

Gay-Crosby, whose children are now 12 and 14, went on to say the quality of the schools is important to her. “The school system here is really good. The actual neighborhood and community is also very diverse and I wanted them to have a similar experience to what I had when I was growing up. So I felt Columbia is still a good choice, which is why I came back.”

Gay-Crosby describes feeling a sense of allegiance. “I felt like I kind of owed something back to Howard County for all the things I had gotten [from living here].”

Gay-Crosby’s father was president of the local chapter of the NAACP when she was in elementary and high school and chairman of the board for the Howard County Center of African American Culture, she says. “I felt like he wanted to make sure he was creating a community that he wanted my sister and me to grow up in. He was very deliberate in making sure that happened.”

Her father confirmed that it was deliberate: He and his wife had already had some experience living in a planned community near Pittsburgh—Garden City—and had lived in other cities, as well. They knew what they wanted.

“We decided to move to Columbia, quite frankly, because of the school system,” Gay says. They also liked the fact that Columbia is equidistant from Baltimore and Washington, D.C. “Those two markets would make it pretty easy to do job searches if that became a necessity,” he explains. “And my wife Doretha is an educator. She was very pleased to begin working in the school system when we transferred here.”