Research has shown that interaction with a pet is beneficial on many levels

STORY BY Elizabeth Heubeck PHOTOGRAPHY BY Mary C. Gardella

September/October 2017

When I was 4, I felt certain that my friend’s two dogs were horses. They were taller than I, with pointy ears and sharp teeth. They smelled of swampy  muck and terrified me. Then there was a neighbor’s German shepherd, who raced back and forth on the front porch, barking when we walked past. Upon visiting my future in-laws for the first time, their son and I were greeted by two enormous Labrador retrievers whose barks convinced me they could rip me to shreds. They never bit me, but they did maul a brand-new pair of flats I naively placed by the door.

muck and terrified me. Then there was a neighbor’s German shepherd, who raced back and forth on the front porch, barking when we walked past. Upon visiting my future in-laws for the first time, their son and I were greeted by two enormous Labrador retrievers whose barks convinced me they could rip me to shreds. They never bit me, but they did maul a brand-new pair of flats I naively placed by the door.

I never envisioned myself a dog owner.

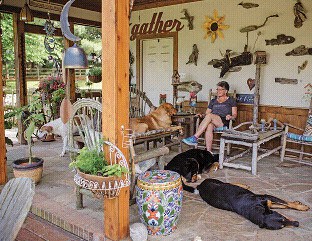

That changed when my daughter, 12 at the time, begged us for a dog. An animal lover from the time she could play with stuffed toys, she promised to fill out the paperwork to adopt a rescue dog and train it. When our puppy dog Sadie came into our lives, every member of our family developed a special relationship with her. Our loving and sensitive mutt has changed the way I perceive pets.

My drastic change in attitude mirrors a shift over the past several decades in how Americans view their relationship with domesticated animals. In our grandparents’ generation, most people acquired dogs to serve primarily as guard dogs or, in rural areas, for hunting. Dogs lived in simple, outdoor houses or in a barn or garage. Now, most American dog owners wouldn’t think of leaving Fido outdoors all day. Instead, we buy expensive dog beds where they can lounge at will, even though upwards of 80 percent of dogs sleep on—or in—their owners’ beds at night.

In 2016 alone, Americans doled out more than $60 billion on pets, according to the American Pet Products Association (APPA). That number is likely to keep rising as pet ownership continues to trend upward. Currently, about 85 million American households, or 68 percent, own a pet, reports the APPA. This is up from 58 percent 30 years ago.

Life-long animal lover and veterinarian Estelle Ward, co-owner of West Friendship Animal Hospital, provides a simple explanation for the morphing relationship between humans and their four-legged friends: “Companionship is really the cornerstone” of the pet–person relationship, she says. A pet, she says, “can be a stead¬fast anchor in a complicated world.” says Ward.

From anecdotes to data-driven research, there’s plenty of evidence of the positive—some might say downright healing—effects animals on humans. Some researchers call this “the Lassie effect.”

From anecdotes to data-driven research, there’s plenty of evidence of the positive—some might say downright healing—effects animals on humans. Some researchers call this “the Lassie effect.”

A study in Australia recently found that regular dog walkers were more likely to meet the recommended 150 minutes of physical activity per week. Moreover, the study found, support systems like neighborhood dog parks increased the dog owners’ likelihood to walk.

With their profusion of bacteria, dogs, the “New York Times” recently reported, can add diversity to the indoor microbiome. Before you banish your pup to the bathtub, note the growing evidence that exposure to a range of bacteria can help prevent auto¬immune disorders and allergies. Jack Gilbert, director of the Microbiome Center at the University of Chicago and an advocate of pet ownership is quoted in the “Times” as saying, “If we can’t bring our kids to the farm, maybe we can bring the farm to kids.”

And of course, domesticated animals also provide a wealth of emotional benefits—even for non-pet owners.

Pets on Wheels, a Maryland-based organization utilizes volunteers and their therapy dogs (not to be confused with service dogs, which receive much lengthier and specific training) to provide uplifting visits to people in a variety of settings. The therapy dog may lie at the feet of a young reluctant reader at a local library as he or she reads out loud to the nonjudgmental listener. Or, the dog may receive a gentle petting from the resident of a  nursing home. The power of touch has been shown to have therapeutic benefits for elderly patients with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

nursing home. The power of touch has been shown to have therapeutic benefits for elderly patients with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

According to Gina Kazimir, executive director of Pets on Wheels, as many as 60 percent of seniors in nursing homes don’t receive regular visitors. “It’s an incredibly sad situation,” she says. “Simply by visiting, you’re providing an amazing service.” Kazimir has witnessed the profound effects that therapy dogs can have on the people they visit. She has seen older people with dementia regain their desire and make attempts to speak. She has heard from parents who say their children’s willingness to read independently increased after a few sessions spent reading to therapy dogs.

Shari Sternberger co-founded National Capital Therapy Dogs in Highland more than 20 years ago. From the way she talks about her experiences as a therapy dog handler, it’s hard to tell who benefited more from the experience: she or the people her dogs visited.

“Whatever we had on our shoulders that day kind of fell off,” Sternberger says of the precious time she and her husband, Wayne, spent with their therapy dogs and various patients, often at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center and Johns Hopkins Hospital.

She describes a young girl in the hospital with cancer. The girl’s mother hesitated to let the child pet the therapy dog waiting patiently in the doorway. Eventually, the young girl’s father allowed Sternberger and the dog to enter the room. Sternberger recalls the girl’s radiant joy as she caressed the dog. Sternberger says she is grateful the girl, who did not recover from the disease, had an opportunity to experience a tender moment with a pet.

If you own a dog, you have probably experienced its ability to sense and respond to people’s moods—especially their owners’. Pets on Wheels’ Kazimir recalls how her dogs behaved when her late father-in-law was ill. Normally, the high-energy hounds would roughhouse and run with her husband.  But, Kazimir says, during that period they sensed her husband’s melancholy mood and, as she put it, “they suspended all of their needs.” Reflecting on what seems to be a dog’s sense of intuition, Kazimer says, “The reality is that dogs read body language in a way that humans simply can’t.”

But, Kazimir says, during that period they sensed her husband’s melancholy mood and, as she put it, “they suspended all of their needs.” Reflecting on what seems to be a dog’s sense of intuition, Kazimer says, “The reality is that dogs read body language in a way that humans simply can’t.”

And yet, these pets that we bring into our homes—our beds, even—to love unconditionally and treat as family members, are animals. And this is something, veterinarian Ward reminds us, that we too often forget.

“We need to monitor the level of anthropomorphism that we bring to the table,” says Ward. After all, pets often revert to instinct—witness such small “presents” as birds and rodents left bloodied on your stoop, or the aggression some dogs can display when encountering a foe. “These are dogs or cats in their own right,” Ward points out. Even though she adds, “We all just adore them.”