A TEENAGE DAUGHTER CAN HELP YOU LET GO AND LET GRAVITY

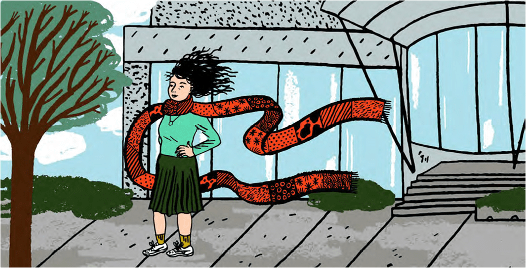

STORY BY Christine Grillo ILLUSTRATION BY Paige Vickers

June/July 2017

“Maybe you could be the artsy mom.”

This was my teenage daughter’s best attempt at compromise. After she turned 13, she started longing for a stylish mom, or a fun mom, or a mom who likes the mall—and I was a brutal disappointment.

“I guess you could wear long, funky scarves,” she said sullenly.

I admired her effort to find something she could work with. As she has metamorphosed into an entirely new person— a teenager—we have tried to find things to admire about each other. The bad news is that this is a daily struggle for both of us. The good news is that metaphorically holding her hand while she walks through her teenage years is making me feel a lot better about my own middle age.

She used to be the coolest little kid, the girl of my heart: She made art with garbage, she sang instead of talking, she wore leopard print with stripes with paisley. Now, right on schedule, she’s obsessed with perfect eyebrows and the exact, right Patagonia pullover and for some reason I will never understand, “Gray’s Anatomy.”

“Why can’t we be like Lorelai and Rory in “Gilmore Girls?” she asks.

What I growl inside my throat is, “Because Lorelai is a self-absorbed pain in the neck who never stops talking, and Rory is boring.” (I’m not brilliant, but I’m smart enough not to say that out loud.)

She makes me feel like an insane person. I walk into my bedroom and find all my T-shirts on the floor—because apparently she didn’t have any good T-shirts and thought I might. I’m rushing to get to work and need to tweeze something, and I can’t find my tweezers, which I always leave in exactly the same place—she needed them and doesn’t remember where she put them.

Very steadily she is disabusing me of the notion that there is such a thing as mine, as in, not hers. Apparently, everything that is hers is hers, and everything that is mine is hers. The items I really don’t want to share (fancy chocolate! expensive lipstick!), I keep in a shoebox in the bath¬room closet labeled Cleaning Supplies. She will never open it.

Naturally, it’s a two-way street. I drive her insane just by being my normal, embarrassing self. To wit: That time I took her to the mall, and when she noticed my outfit for the first time in the parking lot, tears sprang to her eyes.

“Please tell me that’s not what you’re wearing into the mall,” she whispered. “Please.”

I checked my outfit. Is it really so terrible, I asked her, that I’m wearing a skirt with running shoes? We got back in the car and went home, because her mortification was greater than her need to shop.

There was the time I picked her up at a friend’s house at 11 o’clock at night and never got out of the car. She turned her head, noticed I wasn’t wearing a bra and told me that all of Baltimore could see how obscene I looked without a bra. And there was that time when I picked her up from class and she looked me up and down and curled her lip.

“You look like you got dressed at a yard sale,” she said.

Phew, I thought, it’s only yard-sale bad.

We have conversations about life choices:

Her: “Are we ever going to be rich?”

Me: “No.”

Her: “What were you thinking when you decided to be a writer?”

We have conversations about my parenting skills:

Her: “I hate my science teacher so much and I want her to die.”

Me: “Wow, those seem like some very strong feelings.”

Her: “Those seem like some strong feelings. Did you learn that in the parenting textbook?”

We have conversations about feelings:

Me: “We’ve spent three hours talking about how much you dislike me. I’m tired, and my feelings are hurt and I have to go to bed.”

Her: “Oh, so you don’t want me to express myself? Fine. I’ll just bottle it all up inside.”

But she has started making an effort to be more kind. The other day she walked into the kitchen and said, “Hey, you cleaned. It almost looks nice in here.”

When I tell my friends about our relation¬ship, they’re amazed that I tolerate so much. Then I explain that it’s not hard—I don’t take any of her struggles personally. She’s behaving like a jerk because it’s the most efficient way for her to figure out who she is. And as I watch her go through this tedious, ridiculous process of trying to figure out who she is, I feel empathy. It’s a horrible, terrible, no-good job, this busi¬ness of defining yourself.

Teenagers are in the process of figuring out what they like, who they like, what they believe, what makes them laugh. Until then, they are shapeless, protean masses, black holes of consumption, and nothing feels authentic to them. It’s as if puberty wipes away everything they thought they knew about themselves, and they have to learn everything all over again, like an amnesiac waking up from a coma.

I, on the other hand, know exactly what I like, whom I like, what I believe and what makes me laugh. Well, most of the time, anyway. I’m comfortable with doing what I want and saying what I want, and I don’t care about pleasing everyone any more. I’m not consumed with doubt about whether I talk good enough or kiss good enough. More and more, I channel Popeye: I yam what I yam. That was not an easy place to get to. But it’s a good place—middle age—and I’m trying to lean into it.

I’m losing my looks—but at least I get to watch my daughter become more beautiful every day. My muscles, joints and bones are hitting the skids, too. This became obvious while hiking Mt. Katahdin with my son and his friends a couple years ago; they leapt tall boulders in a single bound while I dug in my pack for ibuprofen.

There’s so much that I don’t miss about being young, and I’m reminded of that every day because I live with people who are carving identities for themselves. They struggle, define, churn; I let go and let gravity.

Sometimes I think that our most pressing pre-existing condition is being human—we age and hurtle headlong to the grave. Little by little, we see our fitness flake away, our quickness evaporate and our skin sag. Mortal¬ity, which seems to reveal itself at middle age, can be depressing. But teenagers help us find the Zen of this stage in life: I enjoy my own company; there’s a world of things I don’t understand; some people don’t like me; I look like I got dressed at a yard sale. It’s all good. Living with teenagers might just be the cure for the middle age.

There is a scene in one of the first episodes of “Girls” that had me hooked. The main char¬acter, Hannah, is in stirrups at the gynecologist, rambling about nonsense and more nonsense. The middle-aged gynecologist sighs and mutters to herself, “You couldn’t pay me to be 24 again.”

My daughter can work and worry all she wants. I’ll keep an eye out for the funky scarf and try to fake my way into “artsy mom.” Maybe some of the fun moms will come over for sangria and we can revel in being done with all that.*