FOR PARENTS OF TRANSGENDER CHILDREN, THE ONLY CHOICE IS HOW TO RESPOND

STORY BY Anne Haddad PHOTOGRAPHY BY Mary C. Gardella

June/July 2017

Probably no parent in history ever looked back on his or her original expectations and thought, “My kid is exactly like I thought she would be.” All the more so for straight parents who learn that their child is gay. And parents who realize their child is transgender say they are in a realm they could never have imagined: Their love for their child is tested, and passing the test means leaving something, or someone else, behind.

she would be.” All the more so for straight parents who learn that their child is gay. And parents who realize their child is transgender say they are in a realm they could never have imagined: Their love for their child is tested, and passing the test means leaving something, or someone else, behind.

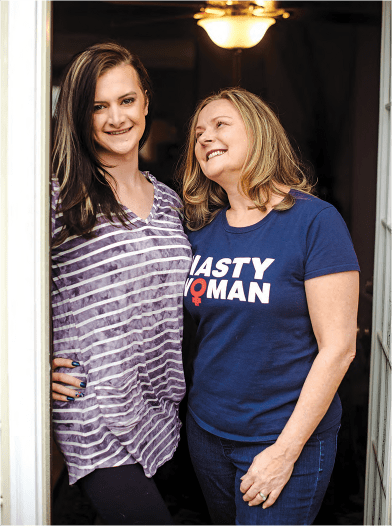

“Many parents think, when we have a child, that they’re going to be a ‘mini-me,’” says Catherine Hyde of Woodstock, the mother of a transgender young woman now in her 20s—a child she named William, after her father, but who is now Whitney. “Our children are not ‘minime’s.’ They’re their own little selves.”

In families whose religion or culture is not tolerant of such differences, most of the members eventually come around to support their LGBTQ loved ones. Not always, however.

“My extended family has basically dis¬owned me entirely because of my child,” says Naomi, a Howard County mother of three who asked that her real name not be used. “They first disowned my son for what they consider his ‘choice.’ To them, this is a sin. They disowned me because I would not disown him.”

Naomi grew up in a very conservative branch of a mainline denomination. She is without a church, but not without faith. Her request for anonymity is to protect her son’s privacy as a public school teacher in another state. She knows that conservative parents or school administrators could make trouble if they learn her son is transgender.

Naomi grew up in a very conservative branch of a mainline denomination. She is without a church, but not without faith. Her request for anonymity is to protect her son’s privacy as a public school teacher in another state. She knows that conservative parents or school administrators could make trouble if they learn her son is transgender.

For Naomi, the irony is that the church she was raised in and that was supposed to be based on love, could not accept that she loved her transgender son enough to accept him for who he is.

.

Listen, Learn and Love

The most important piece of advice from parents of LGBTQ people who have navigated this path is: “Your job [as a parent] is to listen, and learn and love,” Hyde says. “You need to say to them, ‘I’m going to love you wherever you land. When you figure out who you are, whoever you are, I’m still going to love you.”

Hyde is the mid-Atlantic regional director for PFLAG National, an organization of family and friends working with the LGBTQ  community. When her child was 4, she says, he told her that something had gone wrong while he was in her belly, because he was supposed to be a girl. He had already showed a strong and consistent preference for girly things.

community. When her child was 4, she says, he told her that something had gone wrong while he was in her belly, because he was supposed to be a girl. He had already showed a strong and consistent preference for girly things.

“We went to a psychologist, who advised us to discourage girl play and encourage boy play,” Hyde says. In retrospect, she says, those attempts to redirect Will’s gender identity only shamed her child.

“Will became a very sullen child, and at age 6, told me ‘Mommy, I’m going to get a real gun and kill myself,” Hyde says. “We went back to the psychologist, who diagnosed anxiety and depression and said our child might be gay and asked if we were OK with that. We were. We didn’t even know it was a gender issue.”

At age 15, by then out as an effeminate boy who was attracted to other boys, Will told Hyde that he had the best of both worlds—a boy on the outside and a girl on the inside.

Upon hearing him say that, “In a fit of pique, during an argument, I told Will, ‘You can be as gay as you want, but if you go ‘trans’ on me, it’s going to be out of my house and on your own time and money!’ ”

Hyde tells this to other parents to illustrate that even she, as enlightened as she felt she was by that point and accepting of a gay child, had said the wrong thing out of fear and ignorance.

“I was horrified over what might happen to my child,” Hyde says. “I had never met a transgender person.”

“I was horrified over what might happen to my child,” Hyde says. “I had never met a transgender person.”

A few weeks after her outburst, she happened to be listening to public radio programs in which transgender children and adults were saying—almost word for word—things that Will had been telling her since he was 4.

She learned about puberty-blocking drugs and their ability to “pause time” for young transgender teens to figure them¬selves out. She and her husband decided to have “the trans talk” with Will and to offer the option of puberty-blocking drugs.

“But by then, the gender conversations in our house had become so raw that Will responded immediately and force¬fully, shouting, ‘No! Can I go back to my room now?’ ” Two hours later, says Hyde, “Will sought me out to say, ‘I want those things that can pause time.’ And our journey began.”

The parents started to read everything they could get their hands on. Hyde learned about the Gender Spectrum Family Conference held in Seattle in 2008 and spent $3,000 to take Will there.

“It was the first time my child met other children like her. My kid could feel like she’s not a freak,” Hyde says. “It was just life-saving. I said, ‘I want this on the East Coast.’” Three years ago, Hyde helped to launch Gender Conference East in Baltimore. This year, it’s in Newark, New Jersey. The conference is held in different places so that more families can have a chance to attend, Hyde says.

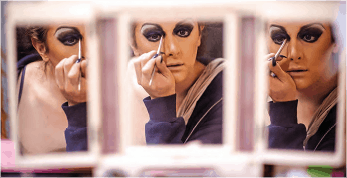

For Will’s 17th birthday, Hyde took her to the popular weekly Sunday morning drag brunch at Perry’s, a restaurant in Washington, D.C. Her teen, who had trained as a dancer all through high school, had dressed to the hilt, Hyde said, in a short skirt and sexy top. During the brunch show, she accepted an invitation to perform— choosing a Lady Gaga song—and earned $52 in tips. Will, who is now Whitney, performs regularly at the brunch under her stage name, Whitney GucciGoo.

.

Re-Examining Faith

Re-Examining Faith

Naomi has accepted her oldest child as a transgender man, now 24. Even her mother, who disowned her grandchild for “choosing” to live as a man, has been prompted by the approaching shadows of mortality to attempt to reconcile, but not with full acceptance.

Naomi continues to wonder if she will find a new faith community that fits her.

Naomi continues to wonder if she will find a new faith community that fits her.

“I sort of have PTSD about churches,” she says. “I never lost faith in God. What was so hurtful was that in my time of need I felt betrayed by the [church] community that was supposed to be a loving family.”

Naomi first learned of her child’s anguish, a girl attracted to other girls, by finding a note she was not meant to read. Her immediate concern was that her child needed help. Naomi went to her pastor.

Her pastor and church told her that homo¬sexuality is a disorder linked to many risk factors, one of which is a broken relationship with the parent of the same gender. The pastor told her that she, Naomi, was to blame for her daughter’s sexual identity.

For Naomi, the church was the center of her life. “I had a very small world,” she says. “Basically, every time the church doors were open, we were there.” An engineer, she had left  work to be a stay-at-home mother and church volunteer and even served on the church staff for a period. And now she was being told that she had failed at her most important job—being a mother.

work to be a stay-at-home mother and church volunteer and even served on the church staff for a period. And now she was being told that she had failed at her most important job—being a mother.

Naomi went in search of a therapist who was Christian and would counsel a gay youth, and the closest one she could find for her child was in Annapolis. Naomi thought her child was in “reparative” therapy, but later discovered it was not. Meanwhile Naomi went through the parent version of reparative therapy.

Naomi did as she was counseled to do—planning more mother-daughter time with her oldest child, for example, taking her shopping, to “repair” the relationship. The result was positive, in fact, but Naomi wasn’t able to see it. Her teen brought home new gay friends.

And, Naomi was instructed by her therapist to build relationships with them too, to compensate for the broken relationships they must have suffered with their own parents.

When her oldest went away to college and eventually came out as a transgender male, Naomi told her pastor.

She heard the word “excommunication” come from his mouth. She was devastated, but she chose to break with the church rather than with her child.

Support from other parents through PFLAG and the Gay Christian Network has helped to fill the void of the church she left.

“My exposure to gay Christians was very eye-opening to me,” Naomi says. She has since realized that being a gay person is not a choice and can be agonizing for those who are not accepted by those around them. She knows now, she says, that you can’t “pray the gay away.” This realization, she says, “has made all the difference to me in accepting who my child is.”*

Whitney Gallucci and her mother, Catherine Hyde. The most important advice most LGBTQ people give is, “Listen, learn and love.”